[Originally posted as a response on the Read 2.0 discussion list]

It’s fair to say that ebooks are here to stay, but it’s also pretty obvious there’s a lot of hot air floating around.

A provocative article from Wired I saw today points out the remaining painful flaws with ebooks. It got some backlash among fans.

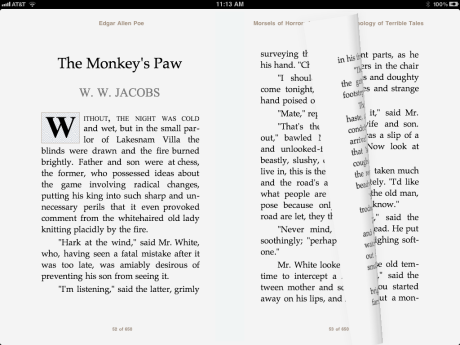

The way I read it, the second time through, was not that the basic premise is ebooks should replicate the print world, but they should evolve from the best traits of the print world, and then add some new ones of their own.

I think all of his points are extremely valid criticisms of nagging problems with ebooks as a medium.

1.) They still feel ephemeral. E-ink does something to alleviate this. I place my Kindle on top of my stack of unfinished paperbacks. That’s my reminder there are 5 more unfinished e-books there. Placing my iPad there wouldn’t make as much sense.

2.) The first point leads nicely into the second one, which is why can’t all the lovely Epubs I read in iBooks be available on my Kindle? You have to admit, the selfish segmentation of content according to hardware and/or retailer is one of the stupidest and most annoying problems that the industry is perpetuating.

3.) The margin note problem is in turn related to device segmentation as well. Currently, even in the new Epub 3 spec, the industry is resisting the ability to connect a book to the wider universe of the social web. The ideal container is designed to restrict what we can do with the content and what other data we can bring into it.

4.) Pricing is still a valid concern, and an industry problem. I don’t think anyone on this [Read 2.0] list would dispute that.

5.) On this point, I agree with a fundamental assumption, which is that books, unlike other media, are inherently physical. And I don’t just mean covers and spines and paper. E-ink, remember, has physicality to it. It’s not just light emitted from a screen, it’s light reflecting off of particles. It’s the most natural successor to the printed page. It’s a testament that we can’t discount the value of jackets, spines, and form factors in figuring out where the ebook is headed. The question of whether consumers will continue to want pretty packages for their ebooks has not yet been resolved.

Rather than being superfluous, I think this article raises important concerns in layman’s terms, and it’s refreshing to have it as a backdrop to all the hype. We have a long way to go…

Aaron

You must be logged in to post a comment.