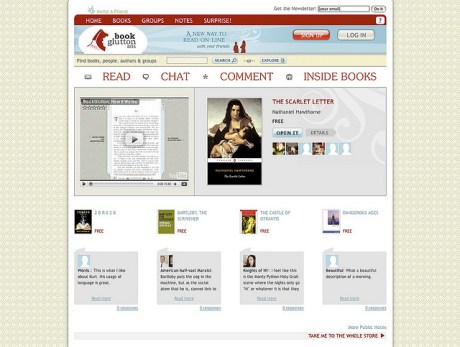

Some startups are driven by money or market control, but BookGlutton was created out of a passion to help people appreciate what they read. Its mission has always been to make reading books more like the way we read, share, and discuss other content.

Since 2007, BookGlutton has delivered an innovative social reading experience. For many years, it was the only way people could discuss a book right from the page. Shared commenting has always been a core part of the experience.

For 7 years now, I’ve devoted countless personal hours striving to iterate on the BookGlutton experience and technology. It’s been an “interesting” ride with many ups and downs. Both my co-founder, Aaron Miller, and I have learned a lot along the way.

Unfortunately, we now find ourselves unable to fund further business operations and continue to devote our attention to innovating on the site. As of September 7, 2013 all of BookGlutton’s operations and associated services will be discontinued. This includes the website, catalog, unbound reader, widgets, APIs, and EPUB conversion tools.

The site has represented a great innovation in reading and publishing, and we’ve seen it inspire other entrepreneurs and visionaries. I would like to personally thank all of the users who’ve used our products.

For those looking for a replacement for BookGlutton, try ReadUps.com, a new reading experience we’ve just launched. Like BookGlutton, it’s also a social reading system that allows paragraph-level comments and real-time messaging. ReadUps, as a platform, is designed for people to “meet up” inside a book / url / personal writing sample. It’s the evolution of BookGlutton, in a way. But unlike BookGlutton, every ReadUp is part of a single group event, with a set duration, after which the content expires. Inviting people to a ReadUp is as easy as just sharing a URL – and it’s the details like url-based sharing that we expanded on from our days with BookGlutton.

If you’d like to know more, I’ve posted a brief post mortem below, as well as some personal notes about the experience of running this publishing startup.

Sincerely,

Travis Alber, Founder

BookGlutton.com / ReadUps.com

—————

POST MORTEM

HOW IT STARTED

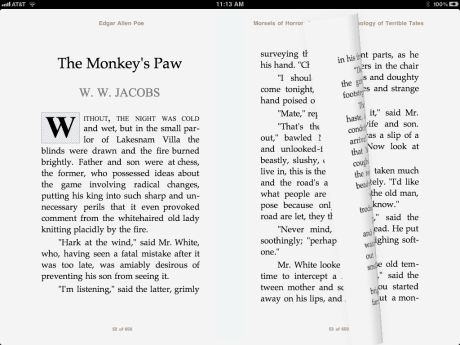

We came up with the idea for BookGlutton in a bar, when we were sitting around complaining about PDFs and the difficulty of actually getting and reading an ebook. (Isn’t this what everyone talks about it bars?) The crux of the argument: “why can’t you share and discuss a book like you can a movie or webpage?” We wanted to read a book in a browser, like we read news, email, and blogs. We wanted to leave comments for each other, and, knowing full well that many of these might be snarky, we wanted the ability to shield that from the masses. Ideally we’d even be able to talk in real time if we were in the book together, especially with friends far away, in NY or LA.

In truth, the idea had been building for some time. Aaron Miller and I had lived in Krakow, Poland in 2005. There’s a cool English language bookstore there, but we didn’t have access to many of the things we wanted to read. We also didn’t know many English speakers. We were craving conversations with people about real things (not just how we felt about Polish beer!). We wanted to work our brains a bit.

But the concept began even earlier. Aaron’s master’s thesis had been about the ramifications and logistics of publishing a novel on the web. Part of it was a self-publishing experiment using a homegrown Perl script. This was way back in 1998.

It didn’t dawn on us until much later, not even as we sat at that bar, drawing little boxes on a napkin, that both of us had been thinking about the enormous possibility of books in browsers for most of our adult lives.

As we sat talking about what kind of reading experience we’d want, Aaron said if we can’t find what we want on the Web now, we should just build it. That sounded like a good idea to me.

BUILDING BOOKGLUTTON

At first BookGlutton was going to be a small side project in relation to our other freelance work.

Core features included a reading system built using JavaScript that could parse ebooks in EPUB format. For social features we decided the paragraph was a good unit to attach shared comments, and we also decided to include in-book chat capabilities, limited by chapter.

As we began to build out core features we realized we’d ignored group dynamics. We’d need to have multiple levels of public / private / group reading, and those settings would need to extend to notes as well as the reading system. Moreover, people needed more things to read, so we built a library and started pursuing publishers to get even more content. We built a free converter to help people get their content into EPUB (and our system). We built a widget so people could embed the reading system in their blog (and still log in to limit it to group members). We built in the ability to skin the reading system, create collections and reading lists, and an API to get notes out. Eventually we built an entire publishing platform that ingested ONIX files (metadata catalog files) from publishers. We built in the ability to track usage to get statistics on group growth and other key indicators.

Then we built a store. And a mobile site. And with every new browser that came out, and new devices like the iPad, we redeployed. Although we were smart about how we built it, it was huge.

We were grappling with typical startup growing pains, namely Feature Creep. We had a good process: functionality docs, wireframes, strategy docs, full-on designed templates. But, like many people building the future, we totally overbuilt.

TIME AND MONEY

Three years passed, and we self-funded it. To bootstrap that long meant making some serious personal cutbacks. We whittled down all our personal spending, cashed in stocks we’d accumulated during the dot-com boom, and drained our bank accounts. We moved to a pretty seedy part of town (with drug dealing neighbors) to save rent money and put it toward hosting costs. A guy lived in a van in the driveway next door.

There were many points along the way we should have pulled the plug. But we had plenty of encouragement too. Teachers at NYU and Yale using it in classrooms, NPR interviews, Wired magazine articles, Webby Awards. Partnerships with Random House and O’Reilly Media. Investors calling, other entrepreneurs asking to license our technology. One particularly large company from Seattle cold-called us to suss out our plans, and said we had “deep wells of optimism.” It was probably not meant to be a compliment, but it only spurred us on.

Too many options led to a lack of focus. As the money continued to dwindle, we hooked up with someone who’d come out of a large media company’s M&A department. He believed strongly in the ideas behind BookGlutton, and we brought him on board to spearhead a fundraising round. It was hard to tell if we should raise Angel or Series A. We had only 150,000 uniques a month and a tiny trickle of revenue. But we had just built the first DRM-free, EPUB-only social bookstore, and feeling like that was worth something, we pounded the pavement. We hit both Sand Hill Road in Palo Alto and a number of firms in NYC, making contact with over 200 investors overall. It wasn’t hard to get meetings: the idea was exciting.

But the responses we got broke down into three categories:

- We don’t invest in books – publishing is not a high-growth market

- We’d love to talk to you when you top 1M users or when you’re revenue positive

- Come back when it works on the Kindle.

We never closed a round.

WHAT WENT WRONG

For most startups, there are plenty of factors that work together for you to shut you down. For BookGlutton it included:

- Being too early (we launched six months after Twitter, and two months after the Kindle came out)

- Having a small market size

- Running into difficult content acquisition (publishers couldn’t use our system if they wanted digital rights management, but it’s hard to lock a webpage)

- Realizing complex user expectations (for both content and devices)

- Money (to build awareness or acquire content)

Most of those factors go far beyond our control as founders. After all, we had a great vision for something we’d want to use, and it did inherently have use to thousands of people. But without a strong product/market fit, or money to drive conversion, it’s very difficult to bridge the gap.

NEITHER SUCCESS NOR FAILURE

That brings me to today, and the concept of what it means to not fail and not succeed at the same time. When you’re running a startup, everyone says it’s okay to fail.

“Fail early and often!”

Having done this a few times, I can safely say that 80% of the people who say this are posturing. What people really mean is that you can’t tread water forever. Don’t be afraid to change. Sometimes it’s also hard to define failure. If people still use it, did it actually fail? How much cash do you need to blow through to define failure? Failure is the absolute hardest way to learn a lesson, but you don’t easily forget the mistakes you make running a startup. The ramifications are huge, and often quite personal.

The time for us to move on from BookGlutton was probably two years ago. At that time BookGlutton was 5 years old – ancient for a website. We’d relaunched it twice, but now the chat functionality was overloading the servers – we were going to need to rewrite the entire way chat was handled inside the book, and that was weeks of work. The discussion we had was heated. After years of work, how could we shut it down now, with people still using it? On the other hand, how could we find the time to fix it? By then we’d moved to NYC and had to pay rent.

We talked about joining an incubator and relaunching, but felt our product was too far along. Also, places like TechStars and Y-Combinator require all founders to be on site full time. Since we were married, we were already taking on external work to pay for health insurance and pay our bills. At least one of us needed to have a job. Without time or money, we decided to scrap the chat. In its place we added in Facebook chat – a huge compromise. It didn’t quite do the same thing, and felt different, looked different. It was at that point we started thinking it was time to shut BookGlutton down.

In the end, we’ve spent hundreds of thousands on hosting, development, and lost income. Note to other couples: don’t marry your co-founder – someone needs to bring home the bacon. We postponed starting a family for years, thinking it would be dumb to try to do both. When decisions are being made at that level, failure doesn’t seem like an option. It just means pivot-as-needed. I was willing to work weekend after weekend, month after month. Plenty of people still wanted to use the site, despite the compromises we were making in the product. Four hundred schools used it to study and discuss humanities online. English as a Second language teachers used it for tutoring, in places as far away as Japan. Publishers used it to develop author audiences. Even families were using it to mark up Tom Sawyer together – how cool is that? All the while, large internet companies would check in frequently to see how we were doing. There was the frequent talk of an acquisition. It’s hard to shut something down that people found useful and interesting. Wasn’t that why we built it in the first place?

Today BookGlutton is still only one of a handful of web-based reading systems with extensive social features. So why shut it down?

The answer to that is that we respect our users. If we can’t afford to maintain the technology and plan for future iterations, we shouldn’t run it. People expect something to work, and all the explanations in the world won’t pacify an angry parent whose kid can’t leave a comment because the server’s choking. Also, I personally want to do good work, and if the money and time aren’t there to maintain something, it’s not set up for success.

Some people say what kept us going on it was passion, although close friends called it addiction. In either case, what we’re left with is an affirmation, mainly to ourselves: that whether you build a company or just a site, the beauty of the Web is that you can build what you want and share it with the world.

A lot like a book, really.

Travis Alber & Aaron Miller | August 9, 2013

You must be logged in to post a comment.